Guilty Conscience? Here’s what that means

Although unpleasant and unwanted, the feeling of guilt is common and experienced by us all. Guilt sits in our stomachs, it itches at us throughout the day, and it can cause such stress and anxiety that it can render us sick and tired. Consequently, it is important to understand the function of guilt, and what we can do to reduce guilt when it is unwarranted, toxic, or debilitating.

So, why do we feel guilty in the first place? Guilt is a feeling of responsibility or regret for something that has been done or not done. It is an emotional by-product that emerges when we’ve done something that contradicts the standards others have for us, or that we have for ourselves. This feeling, although uncomfortable and stressful, reinforces that what we’ve done is different from the values we hold, and so it can serve as a reminder to behave better and try harder. Guilt can also encourage social or interpersonal norms, establish a sense of responsibility, validate feelings of care between two people (“if he feels guilty for hurting my feelings, he must care about my feelings in the first place”), and incite action to resolve situations. In these ways, guilt can be good. But guilt is only healthy if appropriate and proportionate to the situation.

Guilt can become problematic when it occurs as a result of something that is out of your hands. For example, if you’ve earned a promotion at a time where your friend just lost their job, you may feel remorse for having success when others are suffering. In this case, however, you did not cause the harm, and so the guilt is unjustified (empathy, for example, may be more appropriate). Another example is survivor’s guilt (which is feeling upset that you survived an event when others did not). It is important to identify justified versus unjustified guilt to curb the presence of guilt that you should not need to carry.

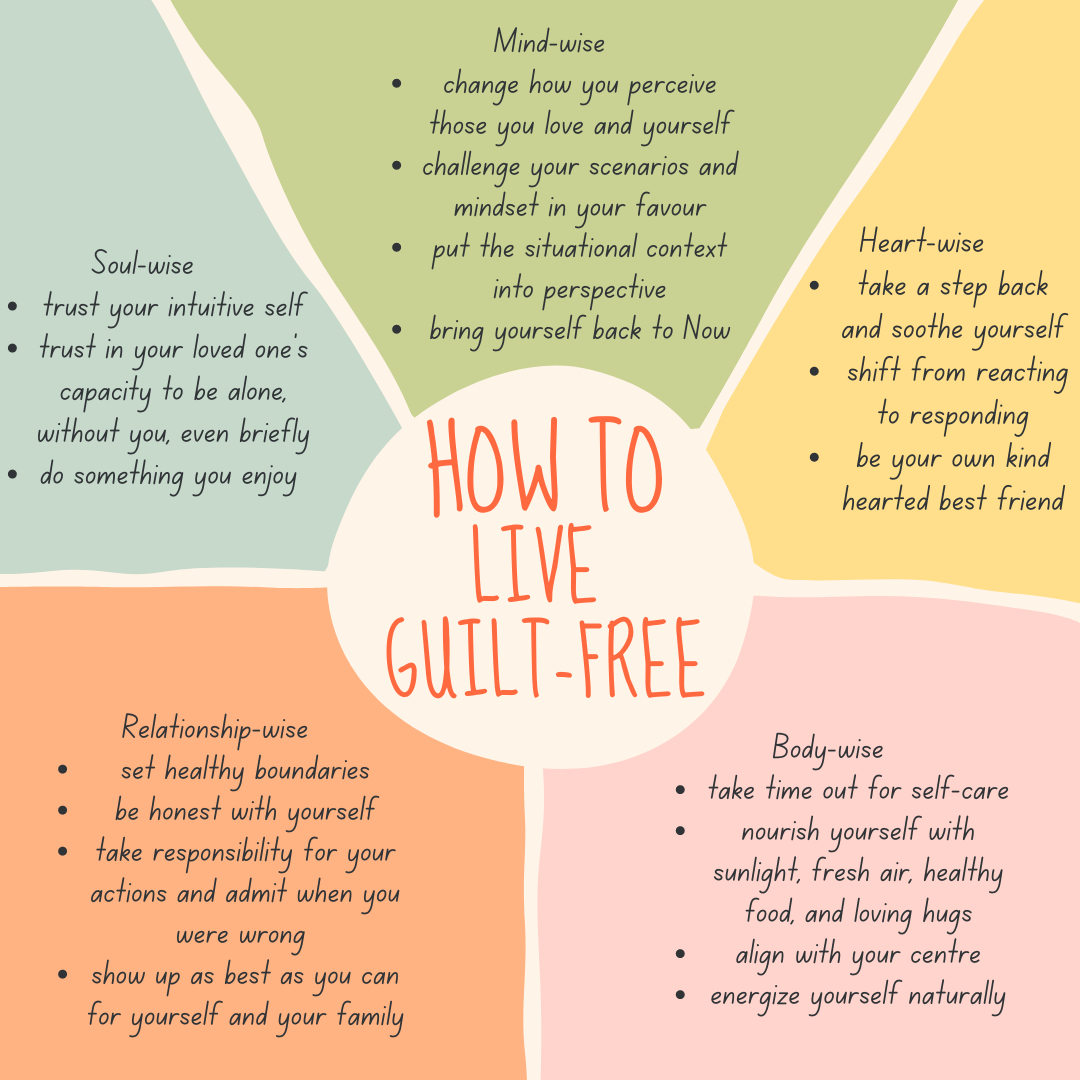

Although guilt can serve as an important social tool and may improve your behaviours in the long run, it can also be exhausting and emotionally taxing if it lingers for too long. Here are some tips for reducing guilt:

Make amends: Apologize if you feel guilty over something you’ve done in the past. If feeling guilty is stopping you from moving forward, taking the time to make amends by calling someone up or asking them to coffee to hash something out can make a world of a difference—even if you think the other person has moved on. Not only will you feel better, but this can incite you to reconnect with a loved one and repair your relationship.

Take the pressure off: Sometimes we feel guilty because we do not always hold ourselves to our values (like feeling guilty because we value family, but do not have time to call our parents every night). Knowing and accepting that we cannot be perfect every day can alleviate the burden. So, telling ourselves that while we want to check up on our parents every night, it is alright that we are busy, and so we can feel happy checking on them when we can, and not because we must.

Set boundaries: Sometimes others can make you feel guilty because you aren’t following their values or doing what they want. It is important to practice some self-preservation by setting clear boundaries and sticking to them.

Know the warning signs: Excessive and irrational guilt may be a warning sign of an anxiety or mood disorder, depression, or other mental health concern. If you notice a pattern of guilt in yourself or a loved one, please consider reaching out to mental health services for help.

–Nazila Tolooei

From Share&Care Summer 2023

Visit amiquebec.org/sources for references

Feelings of guilt can be damaging to a family caregiver’s mental health and can lead to increased stress, anxiety, sleepless nights, and fatigue. Here are some examples of how guilt can be experienced by caregivers of a loved one suffering from mental illness.

- Guilt for not being able to do more, not doing enough

- Guilt for not giving enough time, not providing enough care or support

- Guilt for how we are reacting, treating, behaving with our loved one, e.g. actions taken, words spoken, loss of patience, hovering behaviour

- Guilt for not being able to resolve an issue or prevent our loved one from getting ill

- Guilt for keeping a distance between us and our loved one

- Guilt for the negative impact that the illness has on our family, partner, other children

- Guilt for taking out a court order for psychiatric evaluation of our loved one

- Guilt for our loved one being hospitalized or for saying no when they ask to come home

- Guilt for not being able to comfort our loved one, who may be feeling scared or lonely

- Guilt for no longer wanting to live with our loved one for various reasons

- Guilt triggered by criticism or input from family members or even strangers

Reflecting on these triggers when they produce guilt feelings may help reduce some of the guilt, especially when such feelings may be unjustified.

–Blanche Moskovici, AMI counsellor

Sign up for our emails to stay in touch

Please also follow us on: